1992

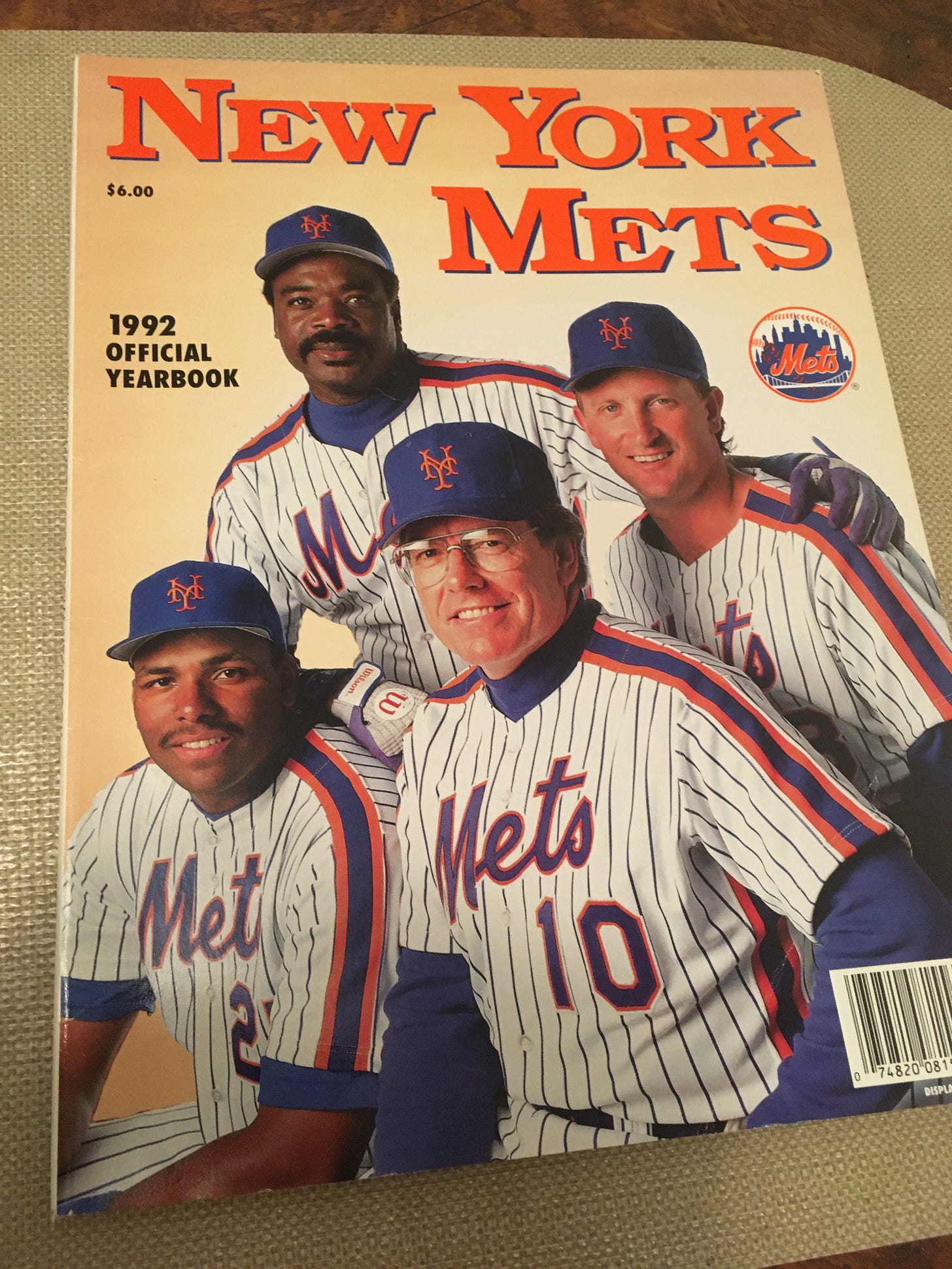

After several winning seasons, the Mets struggled through a terrible 1991. There was no reason to lose hope, however. There are plenty of examples of teams that hit a speed bump and suffer through a terrible season but rebound to get back onto the winning track. The Mets looked primed to improve, as a prolific offseason featured some high profile acquisitions, including the signing of the biggest prize in the free agent class. Unfortunately the front cover photo from the 1992 yearbook turned out to be as cursed as that old Paul Ryan/Eric Cantor/Kevin McCarthy magazine cover that went viral last week.

All of the men on the cover had their issues in various ways. Jeff Torborg was hired as the new manager to much promise - he was only 2 seasons removed from an AL Manager of the Year award. It’s hard to say how much of the team’s failure was his fault, but suffice it to say that this hiring did not work out.

Bret Saberhagen arrived from Kansas City via trade (farewell Kevin McReynolds and Gregg Jefferies) with 2 Cy Young Awards and a World Series MVP Award to his credit. There was also a narrative to his career as someone who would have a great season in odd-numbered years and a poor one in even-numbered years. In hindsight it’s worth considering that he likely overextended himself in those odd years and would pay the price the following season. You may have noticed that 1992 was an even year & he predictably struggled through an injury marred season. He also broke the pattern with more injuries in 1993. He did rebound with an outstanding 1994, but by that point it was too late to rehabilitate his image among the Shea faithful. And as we will see next year he would also play a part in the behavior that was a factor in creating The Worst Team Money Could Buy.

Eddie Murray was an interesting case. He was well known for being an introvert who just wanted to be left alone to do his job. That job was to produce runs, not to be friendly with the media. That was never an issue in Baltimore, where he spent the first dozen years of his career. There was a respectful distance between Murray and the Baltimore press corps; if he wanted to speak with them on any particular day he would, but if not, no big deal. Writers could always get good quotes from Jim Palmer or Earl Weaver, and later on Cal Ripken Jr. would assume part of that burden. His reluctance to deal with the press wasn’t even a huge issue when he became a Dodger. But the New York media contingent wasn’t having any of that once he signed with the Mets as a free agent. There was a barrage of “why won’t he speak to us.” stories which only served to make him even more moody and withdrawn. Worse, he encouraged some of the younger players to have adverbial relationships of their own with the media, which only served to increase clubhouse tensions. There are two big ironies behind the desire from the press to paint him as a bad guy. First, from a pure onfield standpoint, he was very productive in his two seasons as a Met. Sure, he was no longer the great hitter who perennially appeared near the top of the MVP vote, but he was still a well above average hitter as a Met. Second, he has a well earned reputation as one of the great clubhouse leaders of the sport. Almost to a man everyone who ever played with him described him as one of the very best teammates they ever had. He deserves to be remembered more fondly than he was.

And then there was Bobby Bonilla. It’s not just that he was one of many players (and this phenomenon does not only apply to the Mets) whose production dipped following a splashy free agent signing. The die was cast right at his introductory press conference when he told the assembled press that they wouldn’t be able to wipe the smile off of his face. Well, a lot of things about both his game and his personality were soon revealed. Without Barry Bonds to protect him in the lineup he didn’t hit nearly as well as hoped, and it was already well established that he was a poor fielder. The boos grew louder as his production dropped, and his season was epitomized by two embarrassing moments. Once, the cameras caught him wearing earplugs on the field to drown out the booing. Worse, in one game he was seen phoning the press box in the middle of a game to complain about an error being charged to him. He went on to insult people’s intelligence by claiming that he was actually phoning the official scorer to express his best wishes for an ailing family member of the scorer.

Since there was only so much room on the cover there are a couple of other acquisitions worth noting. The Mets signed Willie Randolph to play second base, which would have been a big coup in 1982, but not so much in 1992. By this point he was essentially a replacement-level player and was out with injury for the last several weeks of the season. 1992 would prove to be his final season as a player.

The Mets also obtained Bill Pecota as part of the Saberhagen trade. Team brass kept telling the fans how much they would love Pecota, and maybe they would have under different circumstances. That type of utility player who can play almost any position has clear value for a winning team, but loses a lot of appeal on a team with a losing record. He was a poor hitter, and would be barely remembered these days had the people at Baseball Prospectus not used his name as the acronym for their projection system.

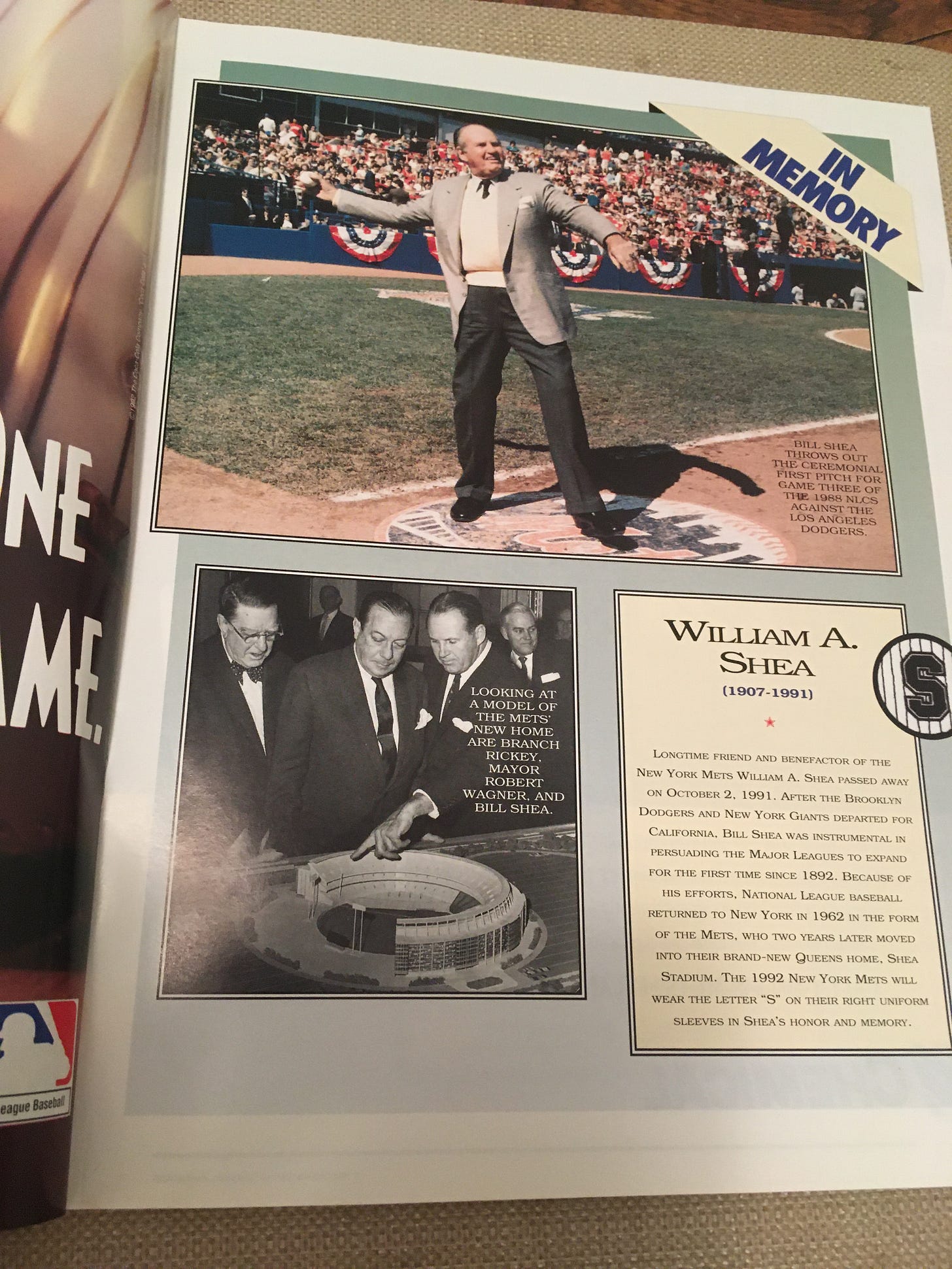

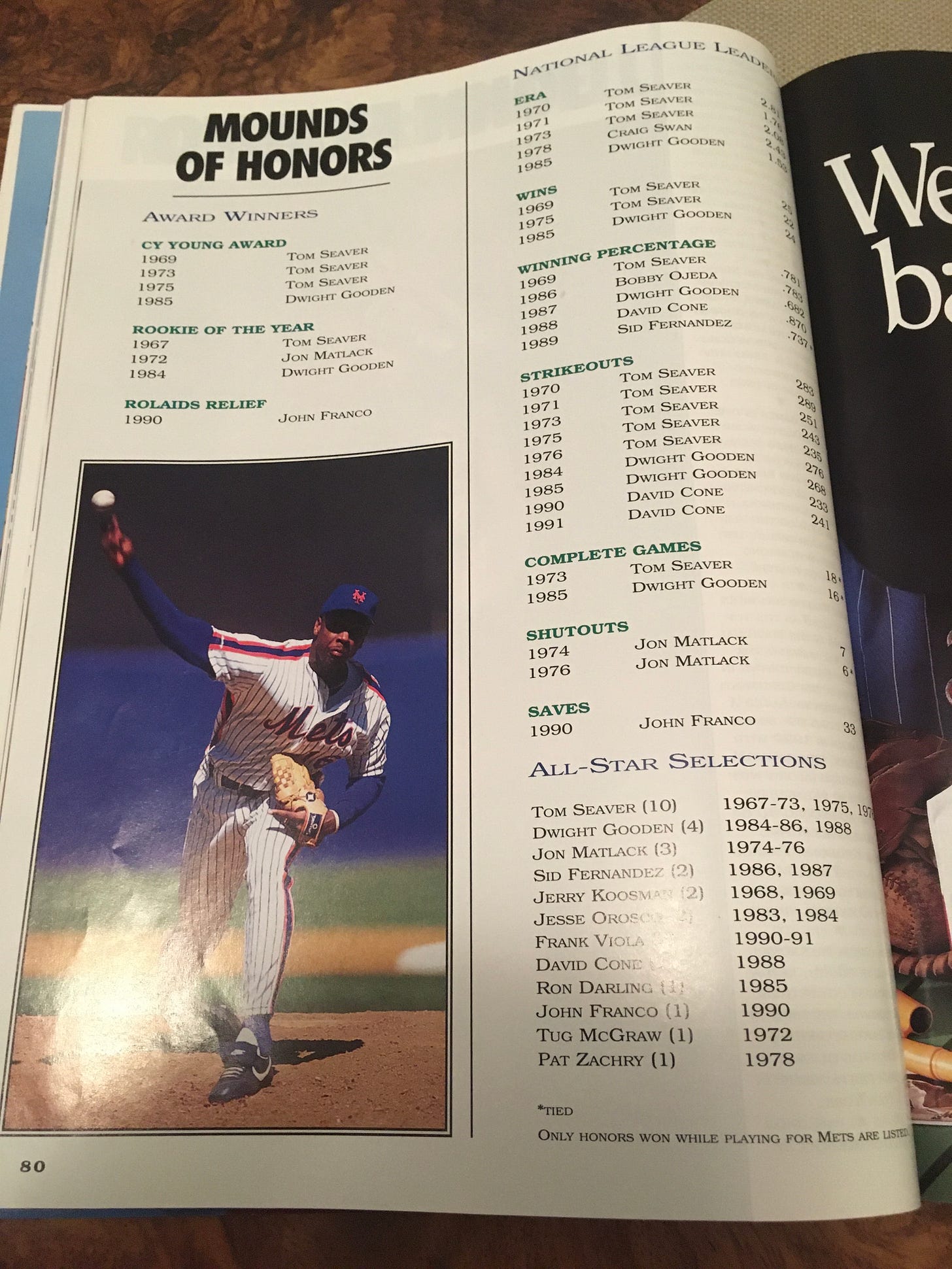

A couple of historical notes were included in the yearbook. First, they paid tribute to Bill Shea, the man who was instrumental in the creation of the franchise and for whom Shea Stadium was named, who had recently passed away. Second, the yearbook included a feature on the team’s history of pitching success and named the 30 Year Dream Staff. (Seaver, Gooden, Koosman, Cone, Darling, McGraw, Orosco, McDowell and Franco.) I’ll also give the editorial staff for searching for silver linings from the 1991 season. It probably wasn’t easy, but they found a few positive tidbits to share.

But as mentioned, 1992 was a debacle, and would not be the last in this decade. As a sign of the times, the Mets acted as sellers at the trade deadline and sent David Cone to Toronto. That move bummed me out at the time, as it was definitive proof that the good times were over. In return they received Ryan Thompson, a promising prospect who would prove to be a Quad-A type of player, along with Jeff Kent. The mid-90’s Mets was not exactly the greatest atmosphere for a notoriously prickly man such as Kent. He would not fully mature into the productive player that he would be until years after he left Queens.

I should also note that 1992 was Kevin Elster’s final year as a Met. He suffered a major shoulder injury in April and would miss the rest of the season before departing as a free agent. I haven’t discussed him much, even though he was a member of the ‘86 championship team he was far from the most crucial player on that team. But he did produce a notable achievement in his Mets tenure. At one point he had set the record, since broken, for most consecutive errorless games by a shortstop. That record comes with all sorts of asterisks, as a significant number of those games came as a late inning defensive replacement so they were not all full games. But he spent some time in the record books nonetheless.

An historical record of a more dubious nature began this season. Anthony Young began what became the longest losing streak in major league history, eventually ending at 27 consecutive losses. To be fair, he pitched better than that for the most part. He often suffered from terrible luck, but those struggles were emblematic of this chapter in team history.

I’ll close this look back at 1992 on a more humorous note with this photo spread of the minor league managers. Tim Blackwell apparently stepped away from his day job of holding up stagecoaches to manage in A ball. Hell, with the name Blackwell he sounds like he could have been bartending for Al Swearengen. And looking at the Steve Swisher photo makes me wish that he & Nick Swisher had had some sort of Freaky Friday body switch. It would have been comedy gold.

So much for 1992. I can’t say that I’m much looking forward to revisiting 1993. That was the year of bleach and firecrackers and showing sportswriters The Bronx and so much losing. So, so much losing.

The Eternal Analytics Debate

1981 World Series - Game 6. Dodgers are leading the Yankees 3 games to 2 & this game is tied at 1 in the 4th inning. Yankees manager tells starter Tommy John that he was going to be removed for a pinch hitter after the #8 hitter was intentionally walked. The ABC dugout cameras caught John walking away from Lemon shaking his head in absolute disbelief. The Yankees failed to score in that inning; the Dodgers proceeded to tee off on the Yankees bullpen and closed out the Series. Premature removals of starting pitchers in playoff games are nothing new.

Loved this Ken Rosenthal piece from The Athletic (behind a paywall) which ran following John Schneider’s already infamous pull of Jose Berrios while he was dealing. I think he describes the issue well, certainly much better than the litany of commentators who spit out the word “analytics” with the same disdain an 8 year old child would use for the word “broccoli.” Ideally, the best way to maneuver a team’s way through a game is with a combination of art and science. I’m fully in favor of using as much data as what’s available to formulate strategy, but as Rosenthal says, feel is ignored too often.

It’s absolutely true that the third time through the order penalty is a real thing. Particularly in the postseason when every game is precious you’re playing with fire if you leave the #3 guy in your rotation in too long. But we’ve lost a lot of the appeal of the sport if even a starter of the level of quality that Berrios isn’t afforded the opportunity to go through the lineup twice, never mind a third time. Let’s be honest, the Jays were swept out of that series because the bats were silent, not because the pitching staff was overmanaged. I still think what happened in that game is a prime example of the game’s tendency to lean too much in the science category over the art one. Preparing a game plan is one thing; I want to see managers set aside the plans more often if the starting pitcher outpitches the plan.

#51

In one sense, Dick Butkus didn’t even seem real. If a scriptwriter were to create a character who was a ferocious middle linebacker for the Chicago Bears, Dick Butkus seems like the ideal name for that character. But he was real, and yes, he was spectacular.

I was just a bit too young to see him play; by the time I learned about him he was more legend than man. In a 9 year career he was a perennial all pro who is still to this day considered to be the greatest to ever man the middle linebacker spot. The recent NFL centennial celebration inspired a plethora of greatest player lists and he ranked in the top 10 in all of them. More than that, he wasn’t just a great player. He had a presence. He’s one of the very first players people picture when thinking of a brutal, ferocious era of the league.

He remained in the public eye well after retirement as he pursued an acting career, and was a prolific commercial pitchman. As an actor, he would often portray a similar character - a classic tough guy. Makes sense, he’s not someone you would think to cast in a revival of a Tennessee Williams play. But if the script calls for a Dick Butkus type? Why not call Dick Butkus? He was often paired with Bubba Smith in such projects as the TV version of the movie Blue Thunder. Several months ago I found myself in a YouTube wormhole and stumbled across this opening credit scene from one of his shows. God, I miss opening credit sequences.

Despite Butkus’ dominance, it wasn’t enough to make the Bears of his era a winning team. They finished near the bottom year after year despite the fact that Gale Sayers was also on that team. Ultimately his career only ran 9 years due to a knee injury. Treatment of that injury caused some hard feelings between player and team, and he was largely estranged from the Bears for way too long. His number wasn’t retired until more than 20 years after he had left the game. It never felt right to see an anonymous linebacker wearing #51 on the field for the Bears. But they eventually did the right thing.

Butkus peacefully passed away late last week at the age of 80. It’s an inevitable product of the passing of time that the memories of many great players fade away as there become fewer people who had actually seen them play. I don’t think that will be the case with Butkus. As long as there will be football, the image of Dick Butkus violently tackling a hapless ball carrier will remain etched in people’s minds.

That’s All For Now

Thanks for reading, and let’s hope for some closer games as the playoffs continue. See you again on Wednesday.